On February 1st, the state budgets for each state will be released, followed by the Union budget for 2023–24. These budgets are extensively scrutinised because they will determine the direction of policy for the remainder of the year.

Following the epidemic, the state of CAPEX and fiscal consolidation

- Rise in the government’s overall budget deficit: We think the focus of the coming years will be bringing the deficit back on track.

- Increasing interest payments: This is crucial since the central government’s net tax income are made up, to an astounding 50%, of interest payments on past debt, leaving very little room for further spending.

- Less room for social spending: It’s critical to gradually reduce the interest burden given the economy’s needs in areas like health, education, and capital expenditure. Fiscal consolidation is the only way to accomplish that.

Examining the national and state governments’ tax revenues and spending

- State revenues have increased more slowly than central government tax collections: Both benefited from the lockdowns, which caused tiny and unorganised businesses to struggle and lose market share to larger businesses that often pay higher taxes.

- Differences in the collection of taxes: Early in the epidemic period, the “special” duty and surcharge on oil accounted for a sizable portion of tax collections, with the majority of these funds going to the central government. To be fair, the federal government subsequently reduced the oil tax (in 2021–22 and 2022-23) and increased the portion of taxes paid by the states.

- Capex of the centre is greater: More current spending has been pledged by the Centre than by the states. While it went up overall throughout the epidemic, the central government’s current spending went up more.

- Spending on social programmes increased: This was primarily due to increased social welfare spending (such as the free food distribution programme) and, more recently, increased subsidies (such as fertilisers) in response to rising commodity prices.

- States have a small capex; yet, it is often believed that they have overspent on unsustainable current expenses. However, the data reveals that just a few states have made significant expenditures (for example, Telangana, Assam, West Bengal and Punjab).

Examining the budget deficit and capex of the federal and state governments

- State capex decreased while central government capex increased: Making a laudable decision, the central government increased capex investment, which increased by 1.2% of GDP between 2019–20 and 2021–22, by using both its tax bonanza and its flexibility to borrow more at a time when banking sector liquidity was loose.

- Reduced state capital expenditures: The states, on the other hand, reduced capex, which has declined as a percentage of GDP over the past few years and is still struggling in the present year. In fact, comparing the capital expenditures of the central government with those of the states and the public sector reveals that the overall public sector impetus is not any greater today than it was in 2018-19.

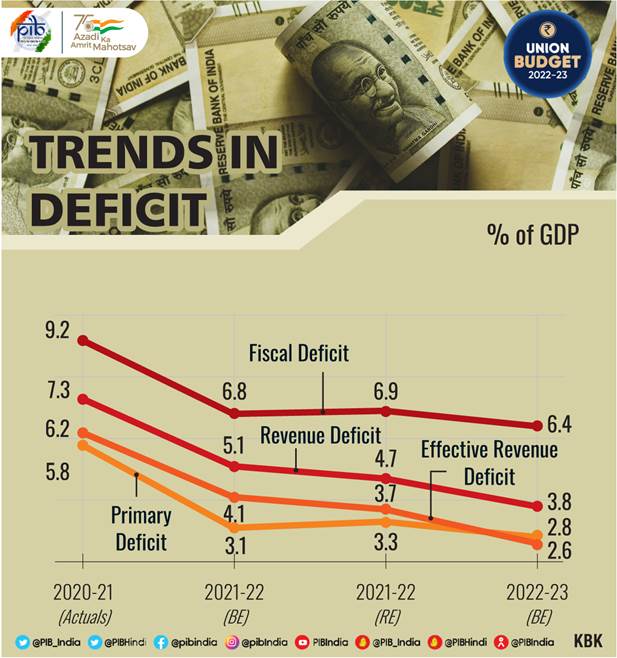

- The budget deficit of the central government has exceeded expectations, although the deficit of the states is largely under control. The central government’s fiscal deficit has increased over the pre-pandemic level of 3.4% in 2018–19 and is significantly above the medium-term target of 3%, coming in at a planned 6.4% of GDP in 2022–23.

- Sharp decline in the state’s target fiscal deficit: The state fiscal deficit increased in the first year of the pandemic (from 2.5% of GDP in 2018–19 to 3.8% in 2020–21), but it has since dropped significantly.

- Low state government borrowing: So far this year, state government borrowing has been relatively low. If this trend holds, the fiscal deficit might drop even further to roughly 2.5% of GDP in 2022–2033, which is substantially below the medium-term target of 3% and exactly in line with pre-pandemic levels.

Challenges

- States’ budget consolidation efforts are limited compared to those of the federal government.

- High quality expenditure: Both face difficulties in committing to greater capex, which is regarded as high quality spending since, when done appropriately, it “crowds in” private investment. And we think that the best long-term strategy to expand the economy’s capacity for growth and job creation is through investment.

- Balancing capital expenditures and budgetary consolidation: The central government faces a problem in maintaining its capital expenditures push during a period of fiscal consolidation. The difficulty for the states is to start acting more.

Way forward

- Fiscal deficit reduction: Over the next three years, the central government wants to reduce the fiscal deficit by roughly 2% of GDP. This consolidation can be partially accomplished by returning current spending to pre-pandemic levels.

- Increasing tax revenue by formalising: Continued economic formalisation increases tax collections, however “organic” formalisation is probably more durable than “forced” formalisation.

- PSU disinvestment: increased efforts to disinvest by selling shares of state-owned businesses and other tax reforms (in terms of direct taxes and the GST).

- Capex reduction is the last choice: If these don’t work, cutting capex will be the only choice left, which is problematic because it could have an impact on medium-term growth.

@the-end

Capital investment and fiscal consolidation ought to go hand in hand. Government funding increases the development of infrastructure, which increases economic growth and employment opportunities. However, this expenditure needs to be done on a solid financial foundation.